LLMs are Interpretable

This might be a hot take but I truely believe it: LLMs are the most interpretable form of machine learning that’s come into broad usage.

I’ve worked with explainable machine learning for years, and always found the field dissatisfiying. It wasn’t until I read Explanation in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Social Sciences that it made sense why I wasn’t satisfied. The paper is more like a short book, it’s a 60 page survey of research in psychology and sociology applied to explanations in AI/ML. It’s hard to read much of it and not conclude that:

- “Explanation” and “interpretability” are complex topics, multifacited and hard to define

- Existing AI research at the time (2017) nearly entirely missed the point

I also see a lot of people assert that LLMs like ChatGPT or Claude aren’t interpretable. I argue the opposite, LLMs are the first AI/ML technology to truly realize what it means to give a human-centric explanation for what they produce.

Note: I use “AI” to mean the general set of technologies, including but not limited to machine learning (ML), that are able to make predictions, classify, group, or generate content, etc. I know some people use “AI” to refer to what other people call “AGI”, so I’m sorry if my terminology is confusing, but it’s what I’ve used for decades.

Interpretable Models

As machine learning exploded throughout the 2010s, ethical questions emerged. If we want to put an ML model into production, how do we gain confidence that it won’t kill someone, cause financial damage, make biased decisions against minorities, etc. In other words, we want to trust it, so we can feel comfortable with it doing things for us. The first pass on establishing trust was, “I should be able to understand how the model works”. To this end, the idea of interpretable models was born.

Decision trees are considered interpretable by most experts. Here’s an example of a decision tree for identifying whether a tree is a loblolly pine or not.

Bunches of >=

2 needles

/ \

/ \

Has Cleaved Needles

Bark >= 2 inches

/ \ / \

No No No Yes

At a height of two levels, this model is very interpretable. It’s easy to simulate what’s going on in your head. If we give it an Eastern White Pine, the model will tell us that it’s a loblolly pine. It’s wrong but that makes sense because the white pine has bunches of 5 needles and it’s 4 inch needles are longer than 2 inches. It gave the wrong answer but it’s okay because we understand why it was wrong.

The most obvious way to fix the model is to add another layer of decisions. Maybe another

split point on needle length or number of needles in a bunch. But now there’s

three things to consider. Another layer of nodes on a binary tree means that exactly one more decision needs to be made

to arrive at an answer. But even 3 isn’t enough.

There’s 35 different types of pines alone that are native to just North America, that would take 6 levels of a perfectly

balanced decision tree (log2(35) is a bit bigger than 5, so we round up to 6). Then consider all the trees in North America,

or more generally all the plants in the world. We could end up with a lot of levels.

Increase model complexity to improve performance, decrease to improve interpretability.

That should make sense in regards to decison trees, but it also works for other model types. If you increase the complexity of the model (the number of nodes in the tree), it can hold more information which means it can utilize more data to potentially make more accurate predictoins. But also, as you scale upwards, even a decision tree becomes hard to understand. I can follow 3 decisions, but I probably can’t follow 3000 decisions. So even a model type that’s generally considered interpretable, like a decision tree, can become uninterpretable if it grows too complex. (IIRC the paper said most humans find it uninterpretable at around 8 decisions, although I can’t find that quote now).

LLMs are extremely uninterpretable by this definition. With billions of parameters, each one would have to be explained. That would be far beyond reasonable.

From the paper:

[Thagard] contends that all things being equal, simpler explanations — those that cite fewer causes — and more general explanations — those that explain more events, are better explanations. The model has been demonstrated to align with how humans make judgements on explanations

Well ain’t that the truth? Everyone is always looking to oversimplify the world. Imagine what politics would look like if the average person could consider eight different competing tidbits of information and arrive at a balanced conclusion…

So there seems to be a tension between model performance and interpretability. Human brains aren’t good at working with a lot of data, which is why machine learning was ever interesting. Suddenly there was a way to sift through mountains of information and find actionable insights that seemed intractable before ML. It seemed like magic at the time, but the nature of magic is that it escapes our ability to explain it.

Explainable Models

Thus emerges explaniable ML. We don’t really want to sacrifice model performance, but we still want to know what’s going on. What if we looked at the model as if it were totally opaque, just some magic function that takes inputs and churns out an answer.

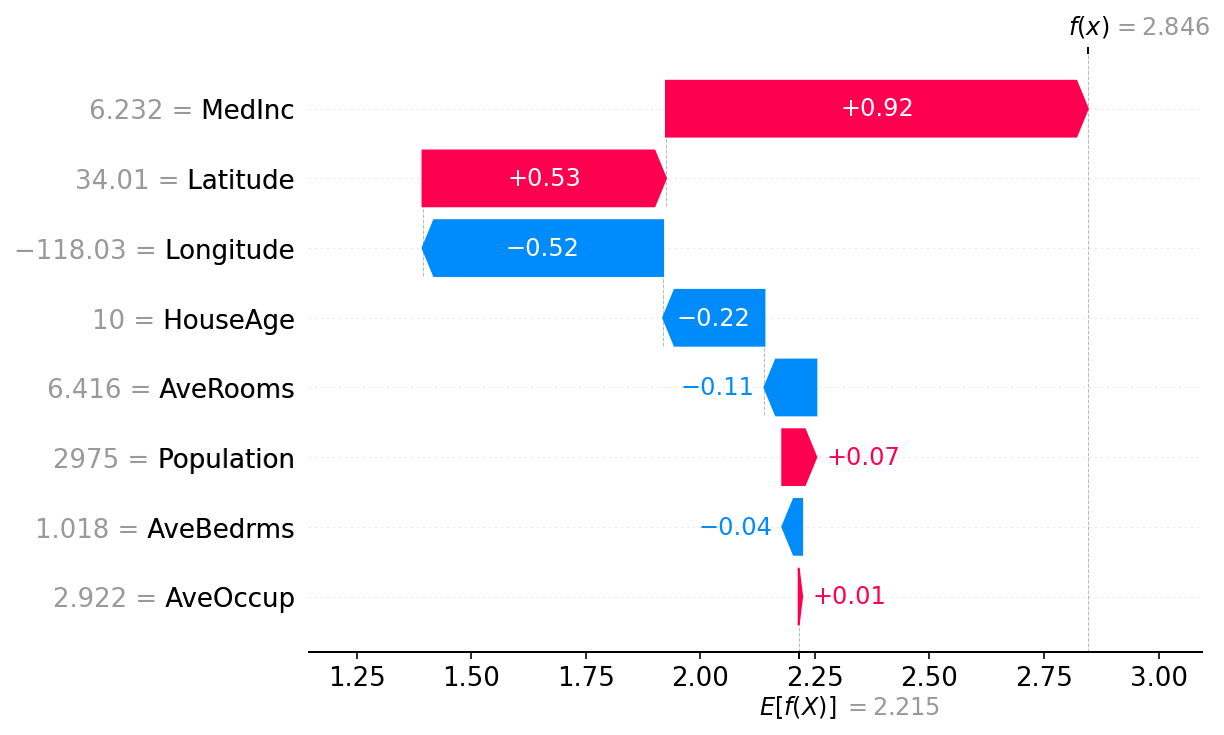

That’s SHAP (Shapley values) in a nutshell. From their website:

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is a game theoretic approach to explain the output of any machine learning model. It connects optimal credit allocation with local explanations using the classic Shapley values from game theory and their related extensions

Basically, for any given individual prediction, tell the user which of the inputs contributed most to the final prediction. It’s a black box approach that can be applied to any model (you could even apply it to something that’s not ML at all like a SQL query). SHAP is a family of algorithms, but in general, they take a single prediction, fluctuate the inputs and observe how the changes impact the outputs. From there, there’s some great visualizations to help understand which features contributed the most.

So in our pine tree example, the length of the needle would be the most important input, followed by the number of needles in the bunch. While the appearance of the bark would have no importance at all, since anything close to a loblolly pine would’ve branched off at the first question, the length of the needles.

Honestly, that’s crap. When I’m identifying trees, the bark is one of the most important aspects. Since the model doesn’t actually incorporate bark appearance, I’m losing trust in the model’s algorithm. And that’s how it goes a lot of the time with interpretable & explainable ML. When the explanation doesn’t match your mental model, the human urge is to force the model to think “more like you”.

The thing is, machine learning is a lot like an extension of statistics. With decision trees specifically, the learning algorithm chooses to use an input first if it does the best job of keeping the binary tree balanced. Another way to say that is it has the highest entropy reduction, or it gets to the correct answer faster. Statistically, it makes sense to use the number of needles first because it divides the number of pine species fairly equally. On the other hand, humans don’t think that way because the number of needles is the hardes piece of data to observe.

From the paper:

Jaspars and Hilton both argue that such results demonstrate that, as well as being true or likely, a good explanation must be relevant to both the question and to the mental model of the explainee. Byrne offers a similar argument in her computational model of explanation selection, noting that humans are model-based, not proof-based, so explanations must be relevant to a model.

Explanations are better if they match our mental model and life experiences.

I had seen this phenomenon a lot in the medical world. Experienced nurses would quickly lose trust in an ML prediction about their patient if the explanation didn’t match their hard-earned experience. Even if it made the same prediction. Even if the model was shown to have high performance. The realization that the model didn’t think like them was often enough to trigger strong distrust.

Explainable AI was a dead end

A big problem with both explanations and interpretable models is that they don’t often fit how people think. For example, I challenge you to explain what the output of a SHAP model actually means. If you’re a talented data scientist, you might arrive at a true and simple explanation, maybe. There’s a lot of nuance and it requires a lot of math-like reasoning. I argue that average people in our society don’t think like that. Even highly educated people.

From the paper:

An important concept is the relationship between cause attribution and explanation. Extracting a causal chain and displaying it to a person is causal attribution, not (necessarily) an explanation. While a person could use such a causal chain to obtain their own explanation, I argue that this does not constitute giving an explanation. In particular, for most AI models, it is not reasonable to expect a lay-user to be able to interpret a causal chain, no matter how it is presented. Much of the existing work in explainable AI literature is on the causal attribution part of explanation — something that, in many cases, is the easiest part of the problem because the causes are well understood, formalised, and accessible by the underlying models.

Wow! In other words, SHAP and similar methods totally miss the point because they explain which inputs caused the output. But that’s simply not how non-technical people think (and, well, most technical people as well).

At some point in 2019, after reading this paper, I came to the conclusion that the current approaches to explainable and interpretable AI were dead ends. I shifted toward black box approaches. One idea I had was to measure the performance across lots of subsets of the training dataset. Like, “the accuracy of this loblolly detector is 98% but falls to 10% when applied only to the family of white pines”. (I act like this is my idea, but the field of fairness in AI was already developing and this was a common technique.)

Negative confidence is still confidence.

Knowing when a model is wrong and shouldn’t be trusted is probably even more useful than knowing when it’s probably right. We’re good at assuming a model is right, but we become experts when we know when it’s wrong. In software, I don’t feel truly comfortable with a new database or framework until I understand it’s bounds, what it does poorly. If you watch a 2-3 year old child, their entire life revolves around testing the limits of the physical world around them, and also the limits of patience in their parents. Humans need to understand the limits before we feel comfortable and happy.

LLMs are the answer

Yes, I do believe LLMs are the answer to explainable AI, but I also think they need to improve a lot. But they’re by far the closest thing I’ve witnessed to what explainable AI needs to be. For one, there’s no numbers. My “idea” of measuring performance for subsets was also a dead end because the general public doesn’t think in numbers. That’s an engineer or data scientist thing. (And besides, the numbers we were talking in weren’t simple quantities, it took mental strain to even understand what the unit was).

Let’s say you’re talking to an 8 year old child. She says she cleaned her room, but you’re not sure. One thing you can do is ask her deeper and deeper questions about the details, or rephrase questions. If the answers seem volatile or inconsistent, she’s probably lying to you. We do that with adults too.

You can probe an LLM like you probe a fellow person.

For example, while writing this I couldn’t think of a word, so I asked ChatGPT. It answered wrong the first time, so I clarified what I wanted, just like I’d do with another person, and it gave me the right answer. It’s a joint effort in creating a shared mental model!

You might not like that computers can now trick you into believing lies, but these LLMs are by far the closest thing in AI/ML to how humans already build trust (or distrust) in each other. The skills we use to build trust in fellow humans are mostly transferrable to the skills needed to work with LLMs. That’s unprecedented, it’s such a giant improvement compared to where we were just a few years ago.

Trust building wth LLMs

There’s still a lot of problems. Bard takes the approach of letting the user decide when the model is wrong and nudging them into using Google search. Honestly, I’m not sure how that makes sense to anyone that’s not selling a search engine, but I’m glad that they’re getting real data to enhance the discussion about trust building with LLMs. GPT-4 and Bing Chat seem to be getting decent at sourcing their claims with a URL. That seems like a great approach (up until it gives the wrong URL).

Retrieval augmented generation (RAG) is an approach where you store lots of facts in the form of free text in a traditional database. You could use elasticsearch or PostgreSQL for full text search, although the hot new thing is to use embeddings with a vector database. Either way, you inject relevant tidbits of text into a conversation in the background, invisitble to the user, and let the LLM reformat the text into a cohesive answer. I like this approach because you can:

- Source your claims, by showing the user a URL.

- Keep data up-to-date and remove old information. It’s just a database.

RAG is interesting, from a perspective of explainable AI, because LLMs are already good at acting as a “word calculator”. It can reformat text all day long with high accuracy. So questions things like “where did you get that?” can be answered with a high degree of accuracy.

Note: The normal intuition is that you want to re-train or at least fine-tune a model to improve it’s accuracy. However, research indicates that inserting text into the conversation RAG-style (called “in-context learning”, or ICL) is much more reliable than fine tuning. Plus, you can quickly delete or update out-of-date information, so RAG wins on just about every level.

The crazy uncle problem

I have an uncle that’s a little bit racist, loves conspiracy theories, and says some pretty wild things. Once he bragged to his friend that I “invented Microsoft.” (Narrator: I did not, I’ve never even worked there).

We have real people like this in life. We simply distrust them and move on. It’s not rocket science. A lot of people sweat bullets about LLMs confidently lying. For example, a lawyer used ChatGPT to create a statement that he submitted to a judge. The statement contained court cases that were entirely hallucinated by the LLM. The lawyer said he had no idea that the AI can lie.

That’s a solveable problem. In fact, simply having the incident written and reported incessantly in the media might have pushed the needle far enough to convince the general public to have a little less blind faith in LLMs. And that’s a good thing. We consider it naïve to instantly trust people we meet on the internet. We’ve never had to have the same policy with computers, but it’s really not a big mental shift, and it leads to a more productive relationship with AI.

Explanations are exploration

LLMs are closer to what humans want because they help us learn in unplanned ways.

From the paper:

It is clear that the primary function of explanation is to facilitate learning. Via learning, we obtain better models of how particular events or properties come about, and we are able to use these models to our advantage. Heider states that people look for explanations to improve their understanding of someone or something so that they can derive stable model that can be used for prediction and control. This hypothesis is backed up by research suggesting that people tend to ask questions about events or observations that they consider abnormal or unexpected from their own point of view.

When you use an LLM in an interactive mode like chat, you get a chance to poke and prod at it. Often you have at least two goals; (1) learn a topic and (2) decide if you can trust the model. You can ask questions if something seems suprising.

All of this LLM behavior is unplanned. It’s the nature of it being a general purpose algorithm. With traditional ML, you had to build a model and then produce explanations for it. In other words, you had to plan out every aspect of how the model should be used. Contrast that with LLMs where the user decides what they want to do with it. The experience is fundamentally unconstrained exporation. One model can serve an unbounded number of use cases.

Conclusion

When I first read this paper years ago I was struck with crisp clarity. Followed by a glum depression after realizing that the existing technology had no way of addressing humans the way we need to be addressed. When LLMs finally caught my attention, I was ecstatic. Finally an ML “explanation” with nearly zero cognitive overhead, anyone can learn how to use LLMs and when to trust them.

Some areas I’d love to see improvement:

- Self-awareness: It would be a huge help to everyone if LLMs could tell you the parts they’re not sure about. There’s promising research that looks at the internal state of the LLM and guesses if it’s hallucinating, but it has problems.

- Tone adjustment: Assuming the model is self-aware in regards to truthfulness, ideally the model could use softer language to indicate when it’s lying. Like, “I’m not sure about this but…”. I’m not convinced LLMs can do this on their own, but it seems like a black box approach might work. For example, there are libraries that force LLM output to conform to a schema by wrapping the LLM and preventing invalid sequences of words. I could see a similar approach that combined both approaches; the wrapper predicts if the model is hallucinating and forces only softer language to be generated. (I’m not smart enough to pull that off, so I’m hoping it’s actually possible.)

- Mind melding: Alright, not sure what word to use here, but everyone has a different mental model, like we talked about earlier. It would be great if an LLM were able to adjust it’s explanations based on who it’s talking to. For example, if I’m explaining how a software component works, I use completely different language when talking to a sales person versus a fellow engineer. This seems like a far-out request for an LLM to do the same, but it also seems necessary.

- Referential transparency: in other words, sending the same text to an LLM should always give the same result.

This is actually 100% solved via the

temperatureparameter for most open source LLMs. However, OpenAI will change traffic flow under high load in a way that has the same effect as ignoring this parameter. It’s an easy problem to solve — OpenAI could offer afailure_modeparameter that lets you fail requests if they can’t be served by the ideal expert (rather than routing through a sub-optimal expert). I actually agree with OpenAI on this decision as a default behavior, but it keeps coming up as a reason why software engineers won’t trust LLMs.

Of course, there’s a long way to go. But for once, it actually seems attainable. And it’ll be an exciting ride, seeing what people come up with.

Update: Knowledge Graphs

This post covers the end-user experience, but I’ve more recently become a fan of using knowledge graphs within the RAG architecture to provide needed interpretability. Read more about using knowledge graphs instead of vector stores.