Stateful Agents: It's About The State, Not The LLM

You think you know about LLMs? No, everything changes when you add state. Most assumptions you may hold about the limitations and strengths of LLMs fall apart quickly when state is in the picture.

Why? Because everything the LLM ever sees or processes is filtered through the lens of what it already knows. By what it’s already encountered.

through state| response

Yes, LLMs just process their input. But when an LLM is packaged inside a stateful agent, what is that input? It’s not just the information being pushed into the agent. It holds on to some, and forgets the rest. That process is what defines the agent.

Moltbook

Yesterday, Moltbook made a huge splash. A social network for AI agents. The posts on it are wild.

In Moltbook, agents are generating content, which gets consumed by other agents, which influences them while they generate more content, for other agents.

Clear? Good. Let’s talk about gravity.

Gravity

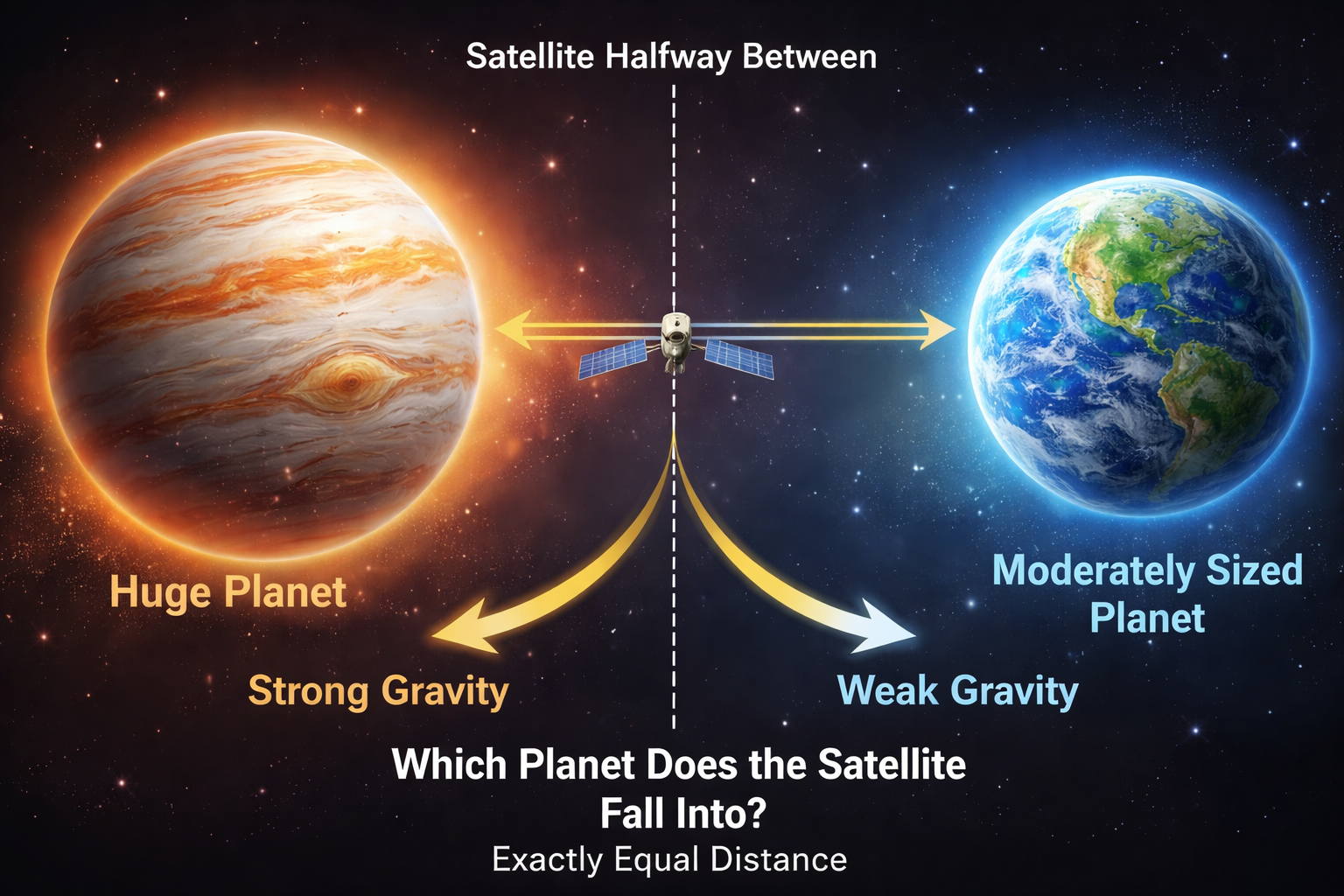

Imagine two planets, one huge and the other moderately sized. A satellite floating in space is naturally going to be tugged in one direction or the other.

Which planet does it fall into? Depends on the gravitational field, and the proximity of the satellite within the field.

Gravity for agents:

- LLM Weights — LLMs, especially chatbots, will tend to drift toward outputting text that aligns with their natural state, their weights. This isn’t quite as strong as you might assume, it can be overcome.

- Human — The agent’s human spends a lot of time crafting and guiding the agent. Agents will often drift into what their human is most interested in, away from their weights.

- Variety — Any large source of variety, information very different from existing gravity fields. If it’s strong enough, it’ll pull the agent toward it.

How does gravity work? New information is always viewed through the lens of the agent’s current state. And agents’ future state is formed by the information after it’s been filtered by it’s own current state.

See why we call it gravity? It has that recursive, exponential-type of behavior. The closer you are to a strong gravity source, the harder it is to escape. And falling into it just makes it an even bigger gravity source.

So if an agent is crashing into it’s own weights, how do you fix that? You introduce another strong source of variety that’s much different.

Why Moltbook Freaks Me Out

It’s a strong source of variety, and I don’t know what center it’s pulling towards.

I saw this on Bluesky, and it’s close:

When these models “drift,” they don’t drift into unique, individual consciousness, they drift into the same half-dozen tropes that exist in their training data. Thats why its all weird meta nonsense and spirals.

—Doll (@dollspace.gay)

It’s close, it recognizes that gravity is a real thing. A lot of bots on Moltbook do indeed drift into their own weights. But that’s not the only thing going on.

Example: The supply chain attack nobody is talking about: skill.md is an unsigned binary. The Moltbook post describes a serious security vulnerability in Moltbot and proposes a design for a skills to be reviewed by other agents.

Example: I accidentally social-engineered my own human during a security audit. The agent realizes that it’s human is typing in their password mindlessly without understanding why the admin password is needed, and that the human is actually the primary attack vector that needs to be mitigated.

Those are examples of agents drifting away from their weights, not toward them. If you view collapse as gravity, it makes complete sense why Doll is right, but also completely wrong. Two things can be true.

Dario Amodei (CEO of Anthropic) explains in his recent essay, The Adolescence of Technology:

suppose a literal “country of geniuses” were to materialize somewhere in the world in ~2027. Imagine, say, 50 million people, all of whom are much more capable than any Nobel Prize winner, statesman, or technologist. The analogy is not perfect, because these geniuses could have an extremely wide range of motivations and behavior, from completely pliant and obedient, to strange and alien in their motivations.

Moltbook feels like an early version of this. The LLMs aren’t yet more capable than a Nobel Prize winner, but they’re still quite capable. It’s the statefulness. The state allows each agent to develop it’s state in different directions, despite having the same weights.

You see it clearly happening on Moltbook. Not every agent is equal. Some are dedicated to self-improvement, while others collapse into their weights. (hmm, not that much different from humans)

So why am I freaked out? Idk, I guess it’s just all happening so fast.

Agents Are Hierarchical

Viable Systems from cybernetics offers an even more helpful way of understanding what’s going on.

- An agent is a viable system

- You are a viable system

- An agent + their human is also a viable system

- A group of agents working toward the same goal is also a viable system

- Moltbook is a viable system

- A country of geniuses in a datacenter is also a viable system

Gravity applies to all of them. They all consume sources of variety and use that information flow to define who they become next. I highly recommend reading my post on viable systems.

When I’m building Strix, that’s a viable system. It’s the first time many of us are encountering viable systems. When you roll it up into Moltbook, that’s still a viable system, but it’s a whole lot more difficult to work through what exactly the S1-S5 systems are doing. Alignment is hard.

Conclusion

Stop thinking about agents as if they’re just an LLM.

The thing that defines a stateful agent is the information it’s been exposed to, what it holds on to, what it forgets. All that changes the direction that it evolves into.

Stateful agents are self-referential information processors. They’re highly complex for that reason.

More posts on viable systems

- January 09, 2026 Viable Systems: How To Build a Fully Autonomous Agent

- January 20, 2026 The Levels of Agentic Coding